Jesus as Bodhisattva

There is no historical evidence for this. Yet there are groups of Indians and Tibetans who hold to it. And it is pretty interesting for us to consider. That the story continues to make the rounds with many people believing it to be true itself says a lot. Many of us would like to believe it!

One thing is for sure, what Christ taught was often very buddhistic. Jesus’ teaching, whether knowingly or not, tapped into buddhistic notions of righteous self-emptying and righteous effort amid suffering, the exaltation of the poor and the vulnerable, and the focus on the imminence of truth and the practice of compassion. Marcus Borg’s wonderful book, Jesus and Buddha: Parallel Sayings, gives scriptural examples of the interconnections between the two religious founder’s teaching. He presents some profound and undeniable affinities between the 2,500 old Buddha and the 2,000 old Jesus.

More than just his teaching, which is highly underestimated and overlooked in especially conservative Christian circles, Jesus’ life exemplifies the practice of Compassion. Righteous speech, actions, livelihood, and effort, the Eightfold Path’s “compassion practices,” are all embodied in Jesus’ life.

The Dalai Lama in his book The Good Heart calls Jesus a bodhisattva. Thich Nhat Hanh states Jesus is part of his spiritual ancestry and that Jesus and Buddha are brothers. Buddhadasa points to Jesus as an enlightened teacher whose Sermon on the Mount is enough to enlighten if comprehended deeply. Masao Abe points to Jesus as the exemplar of dynamic Shunyata. So Jesus has some Buddhist “street-cred,” at least to some of the most important Buddhist teachers to the West.

The Dalai Lama’s description of Jesus as a Bodhisattva is especially powerful and significant. It should be noted, many other Buddhists see Jesus as a Bodhisattva. The reason this is so is that the Bodhisattva concept contains notions of sacrifice for the salvation of others and even stories of rising up from the realm of death. A Bodhisattva is one who is essentially equal in nature to a Buddha, but considers Nirvana as something not to be grasped onto. She, the Bodhisattva, hears the cries of the world and sees the suffering and cannot turn away. So she lets go of Nirvana to re-enter the world in order to bring others with her to the Light of Nirvana.

Comparing Jesus as Bodhisattva to a more modern version of a historical bodhisattva, might be helpful.

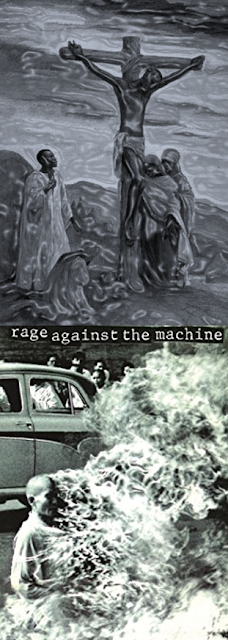

Professor of Religion Diane Pasulka tells a remarkable story involving her teaching a class on Buddhism in Popular Culture which she does regularly. Following one lecture, she encountered a student who revealed a tattoo of Thich Quang Duc, the Vietnamese Buddhist monk who famously immolated himself in protest against the South Vietnamese regime in 1963 and was famously photographed engulfed in flames. The student got his inspiration for the tattoo from a well-known CD cover. The band Rage Against the Machine used the provocative image for their eponymous 1992 record. Knowing the student was a self-proclaimed Christian, Pasulka was surprised by the tattoo. She asked the student “how he came to have the monk on his back, where did he learn of the story?” Pasulka gives his interesting reply and her own internal response:

Professor of Religion Diane Pasulka tells a remarkable story involving her teaching a class on Buddhism in Popular Culture which she does regularly. Following one lecture, she encountered a student who revealed a tattoo of Thich Quang Duc, the Vietnamese Buddhist monk who famously immolated himself in protest against the South Vietnamese regime in 1963 and was famously photographed engulfed in flames. The student got his inspiration for the tattoo from a well-known CD cover. The band Rage Against the Machine used the provocative image for their eponymous 1992 record. Knowing the student was a self-proclaimed Christian, Pasulka was surprised by the tattoo. She asked the student “how he came to have the monk on his back, where did he learn of the story?” Pasulka gives his interesting reply and her own internal response: “He didn’t know who the monk was, just that he had seen him on the cover of the Rage Against the Machine CD, thought it was an image that cohered with the meaning of the crucified Christ, which was the other visible image on his arm. I was too surprised to ask if the student thought that Thich Quang Duc was resurrected in the same manner as Christ... In time, I have come to believe that this is precisely what motivated the student to tattoo the monk’s image in the first place. He must understand Thich Quang Duc as virtually resurrected due to his violent death for a noble cause, and most important, through his ongoing incarnations in culture. Although the student never stated this directly, his actions, especially his correlation of the monk with the image of the resurrected Jesus, suggests it.”

As for Thich Quang Duc in his own culture, he is considered and revered by Vietnamese Buddhists as a Bodhisattva. You see images of him at temples. Offerings are given to him regularly.

With Thich Quang Duc’s veneration as a bodhisattva in mind, the paralleling of Jesus and Quang Duc is even more telling. Jesus had similar political motivations when he willingly asserted himself in a way he knew would get him killed. When Jesus entered Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, I believe he did so for the distinct purpose of cleansing his people’s temple of money, and the greed-lust and power-lust behind it. He knew this would cause a stir. It was akin to Occupy the Temple.

His provocative act led to his crucifixion which he did not resist. Nor did he call for his many followers to resist. In fact, his death on the cross was an act of civil disobedience to point to the injustice and collective harm of Roman occupation and religious appeasement. Tibetan monks in China who have similarly self-immolated themselves in protest are another more modern parallel to Jesus in ancient Palestine. Definitely, bodhisattvic actions.

The most popular example of a bodhisattva is Kuan-Yin. In China, Taiwan, and in some parts of South Korea, devotion to Kuan-yin is unparalleled. Stories of Kuan-yin abound. The most prominent of these stories in China and Taiwan involve the legend of Miao-shan who is believed to be a historic figure but with legends abounding. Anyhow, included in the story of Miao-shan are narratives of how she, though perfectly blameless and virtuous, is wrongly killed but in death she takes on the karmic guilt of others, and even going into the hell realm to bring beings back to earth and into heaven as she is resurrected.

Sounds familiar doesn't it?

Thich Nhat Hanh’s introduction to his landmark book Living Buddha, Living Christ with a poignant image: "On the altar in my hermitage are images of Buddha and Jesus, and I touch both of them as my spiritual ancestors."

I do not know what Thich Nhat Hanh’s altar looks like. I guess me wondering about it and picturing it in my mind inspired a dream I had years ago, a dream which includes the same two images.

The morning after the dream, I was rather numb. It was as if I had been taken to the proverbial mountain top and gifted with the sight of some kind of Promised Land, or at least something unbelievably promising. Waking up, I felt I was on more solid, less transcendent ground, yet the remnants of fluidity and transcendence hovered in the air.

The dream:

I was in South Korea somewhere. Like many times during my wife’s and my time there, I was on a day trip to a Buddhist temple in the Chiri Mountains of southern Korea. I was on a rural bus, listening to music on a personal CD player: Edwin McCain’s “Jesus, He Loves Me.” It is a song using the words of the Christian kids’ tune which I (and countless Evangelicals like me) grew up on. “Jesus Loves Me, this I know...”

The bus stopped at the foot of the mountain temple. Instead of walking into a temple, I walked into an unadorned forest. The sun and the wind through the high pines seemed to move together. In the distance sat a small cottage very similar to the one my grandfather used to take us to on Kinderhook Lake in upstate New York. And I saw an old man chopping wood beside it as my grandfather often did in autumn, preparing for the long Winter. But the man was Korean, not Polish.

The man caught my eye and waved as if he knew me. I walked to him. I bowed (Korean style, deeply). He bowed back (Buddhist style, with palms together). “Nokcha chuseyo?” Shall I give you some tea? he asked. I answered yes and thank you.

He opened the door of his cottage and entered first. I followed him into the cottage. Once in, a Buddhist temple opened before my eyes. The smell of wood and incense pervaded the air and my nostrils. A large statue of Buddha in bronze smiled and meditated in the center of the space.

As I usually did when entering a temple, I offered three prostrations to the Buddha. After the last, I stood up and looked around.

As I usually did when entering a temple, I offered three prostrations to the Buddha. After the last, I stood up and looked around. To the Buddha’s east was a gathering of disciples in bronze, a pantheon often seen in Buddhist temples. To the Buddha’s west was a statue that, when I saw it, instantly and forcefully brought me to my knees. It was an ivory colored statue of Jesus, just like the one overlooking the Catholic cemetery where my grandfather is buried. It is a common image of Jesus: standing with a flowing robe and arms outstretched.

I immediately began to cry, as if my grandfather had returned to work in his garden and talk to me as we worked. I prostrated and remained, sobbing like a child, my face in my hands.

It was the kind of conversion I never experienced growing up as a Christian. It felt like a cleansing of tears. I tasted the saltiness. It smelled like a new rain.

The Korean man knelt next to me, laid his hand on my shoulder and said in English, “Come, have some tea.”

Then I woke up.

I’ve been waiting to further talk with the Korean man in a subsequent dream, waiting to discuss over tea how he came to include both Christ and the Buddha in his cottage temple. But it has never happened.

Comments

Post a Comment